you know how TypeScript has a type system for JavaScript? well,

…

how did we get here?

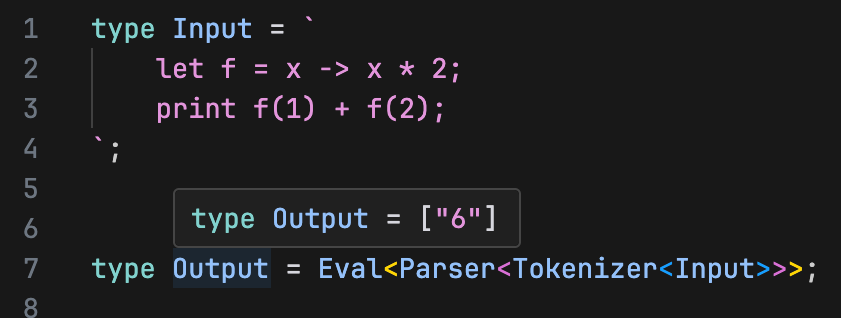

TLTSS: type level typescript script

TLTSS is a basic proof of concept programming language implemented entirely in typescript’s type system. yeah, that’s right, the thing that screams with red squiggly lines when you access a property on an object that you know exists is powerful enough to tokenize, parse, and interpret a programming language. and play doom ???.

features of TLTSS include:

- first class functions and unsigned integers as the only types of values

- scopes

- closures

- mutable variables

- dynamically typed

- basic arithmetic (+ - * /)

- no error handling at all! good luck have fun.

- implemented ~300 LOC

playground

in types?

typescript’s type system is pretty flexible as it lets you have types that are literals. for example, if you wanted to constrain some function’s argument to be either “ease-in”, “ease-out”, or “ease-in-out”, in languages like java you would have the type be string and do a runtime assertion.

function animate(easing: string) {

// ...

}unfortunately, nothing stops you from calling animate("with something bad before runtime"). literal types help us solve this problem.

function animate(easing: "ease-in" | "ease-out" | "ease-in-out") {

// ...

}the type of easing has been constrained to a union of possible literals, and it’s impossible to call the function incorrectly. we also get an error if we call the function with a string we don’t know the value of at compile time, like animate(readUserInput()), which is neat.

typescript lets us make new types from other types, including literal types. we can do so by declaring a generic type on a type declaration. here’s some examples.

type Arrayify<T> = [T];

type Test = Arrayify<21>;

// ^? [21]

type StringifyThreeTimes<T extends string> = `${T}-${T}-${T}`;

type Test2 = StringifyThreeTimes<"hi">;

// ^? "hi-hi-hi"

type FirstElement<T extends any[]> = T[0];

type Test3 = FirstElement<["a", "b", "c"]>;

// ^? "a"this makes use of the extends keyword, which i’ll elaborate on soon.

and we have control flow too. you can have a conditional type dependent on if type A is a subset of type B.

type IsNumber<T> = T extends number ? true : false;

type Test = IsNumber<1>;

// ^? true

type Test2 = IsNumber<"not a number">;

// ^? falseyou might think that’s kinda weird. our only control flow is “is this a subset of that?” but it’s effectively a way of pattern matching, a concept from modern languages. you can think of a type as a pattern, number matches every number literal, 0 | false | "no" matches some falsey things, and the type 0 matches, well only the literal 0.

we can extract inner parts of a type with infer if a “pattern match” goes through.

type FlattenArray<T> = T extends (infer Inner)[]

? Inner

: "T didn't match any[]";

type Test = FlattenArray<string[]>;

// ^? string

type Test2 = FlattenArray<"not an array">;

// ^? "T didn't match any[]"this gets powerful with template literal types.

type ParseColor<T extends string> =

T extends `rgb(${infer R}, ${infer G}, ${infer B})`

? { r: R; g: G; b: B }

: "failed to parse T";

type Test = ParseColor<"rgb(170, 70, 95)">;

// ^? { r: "170", g: "70", b: "95" }since we have control flow, we have a way of breaking out of a recursive type. bear with me on this example.

type CloneUntilLength3<T extends any[]> = T extends [any, any, any]

? T

: CloneUntilLength3<[...T, T[0]]>;

type Test = CloneUntilLength3<["><>"]>;

// ^? ["><>", "><>", "><>"]CloneUntilLength3 will check and see if the input tuple contains three elements, if it does return it, otherwise call itself with a new tuple containing input elements + a clone of the first element.

to recap:

- we can represent literal values in types

- we can create types based on other types

- we have control flow through pattern matching

- we have looping through recursion

these constructs can get us seriously far. they’re part of how your favorite TS libraries give you crazy compile time checks.

(some examples stolen from the typescript handbook)

arithmetic

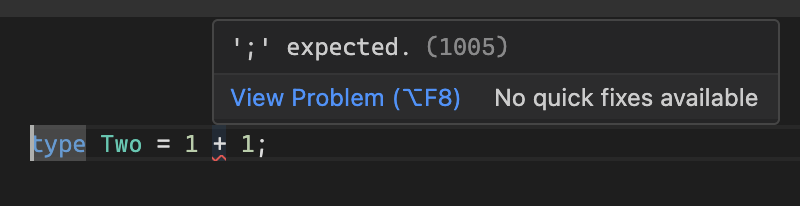

before i get into how the language was made, what happens if we try to compute 1 + 1 in types?

oops, typescript doesn’t have the concept of arithmetic. it just knows number literals exist on their own and nothing else.

there is a very interesting property of all tuples that can help us out here though, and it’s “length”. every tuple has its length stored as a number literal.

type One = ["a"];

type Two = [...One, "b"];

type Three = [...Two, "c"];

type Test = One["length"];

// ^? 1

type Test2 = Two["length"];

// ^? 2

type Test3 = Three["length"];

// ^? 3if we wanted to express A + B, we just need to join two tuples of length A and B together and read its length!

lets make a recursive type MakeTuple<N, Carry> that will check if the current Carry’s length is equal to N, if so return it otherwise recurse with Carry joined with a dummy element to increase length by 1.

type MakeTuple<N extends number, Carry extends any[] = []> =

Carry["length"] extends N

? Carry

: MakeTuple<N, [...Carry, any]>;

type Test = MakeTuple<5>;

// ^? [any, any, any, any, any]Add<A, B> can now join tuples of length A and B to read a new “length”.

type Add<A extends number, B extends number> =

[...MakeTuple<A>, ...MakeTuple<B>]["length"];

type Test = Add<1, 2>;

// ^? 3

type Test2 = Add<999, 999>;

// ^? 1998the limit to this is that TS doesn’t let us recurse more than 1000 times, so Add<1000, 1> results in a very understandable “Type instantiation is excessively deep and possibly infinite”.

i’m sure the people behind early CPUs are really happy computers are fast enough i get to do recursive array clone math to compute 1 + 2 in an interpreted language.

say we wanted to compute 6 - 2, we represent the 6 and 2 like so using MakeTuple<N>.

6: [any, any, any, any, any, any];

2: [any, any];notice how MakeTuple<2> is a subset of MakeTuple<6>? if we just got rid of the subset of MakeTuple<2> in MakeTuple<6>, we would be left with 4 elements, the result of 6 - 2. that’s the wacky idea behind subtraction here.

type Sub<A extends number, B extends number> =

MakeTuple<A> extends [...MakeTuple<B>, ...infer Rest]

? Rest["length"]

: 0;you can think of multiplication as recursive addition. for example A * B is A added to itself B times. Mul recurses while B isn’t zero to add A to a carry.

type Mul<

A extends number,

B extends number,

Carry extends number = 0,

> = B extends 0 ? Carry : Mul<A, Sub<B, 1>, Add<A, Carry>>;and division as recursive subtraction. A / B is the amount of times we subtract B from A until A is zero.

type Div<

A extends number,

B extends number,

Carry extends number = 0,

> = A extends 0 ? Carry : Div<Sub<A, B>, B, Add<Carry, 1>>;making a language with types

foreword, this is not a guide on how to make a programming language but moreso how i did it in types. if you have any interest in languages read Crafting Interpreters by Robert Nystrom, you won’t regret it!

there’s three major steps for TLTSS that look like so:

- tokenizing the source string

- parsing tokens into ASTs (abstract syntax tree)

- interpreting by walking through the AST

tokenizing

my token type is a simple discriminated union. no source mappings, just the token “type” with special data for numbers and identifiers.

type Token =

| { type: "semicolon" }

| { type: "let" }

| { type: "print" }

| { type: "equals" }

| { type: "arrow" }

| { type: "left-paren" }

| { type: "right-paren" }

| { type: "left-brace" }

| { type: "right-brace" }

| { type: "plus" }

| { type: "minus" }

| { type: "star" }

| { type: "slash" }

| { type: "num"; num: number }

| { type: "identifier"; name: string };tokenizing is extremely elegant in type-level TS thanks to template literal matching. i don’t think i could write a cleaner tokenizer in javascript.

type Tokenizer<Input extends string, Tokens extends Token[] = []> =

Input extends `${" " | "\n" | "\t" | "\r"}${infer Rest}` ? Tokenizer<Rest, Tokens>

: Input extends `;${infer Rest}` ? Tokenizer<Rest, [...Tokens, { type: "semicolon" }]>

: Input extends `let${infer Rest}` ? Tokenizer<Rest, [...Tokens, { type: "let" }]>

: Input extends `print${infer Rest}` ? Tokenizer<Rest, [...Tokens, { type: "print" }]>

: Input extends `=${infer Rest}` ? Tokenizer<Rest, [...Tokens, { type: "equals" }]>

: Input extends `->${infer Rest}` ? Tokenizer<Rest, [...Tokens, { type: "arrow" }]>

: Input extends `(${infer Rest}` ? Tokenizer<Rest, [...Tokens, { type: "left-paren" }]>

: Input extends `)${infer Rest}` ? Tokenizer<Rest, [...Tokens, { type: "right-paren" }]>

: Input extends `{${infer Rest}` ? Tokenizer<Rest, [...Tokens, { type: "left-brace" }]>

: Input extends `}${infer Rest}` ? Tokenizer<Rest, [...Tokens, { type: "right-brace" }]>

: Input extends `+${infer Rest}` ? Tokenizer<Rest, [...Tokens, { type: "plus" }]>

: Input extends `-${infer Rest}` ? Tokenizer<Rest, [...Tokens, { type: "minus" }]>

: Input extends `*${infer Rest}` ? Tokenizer<Rest, [...Tokens, { type: "star" }]>

: Input extends `/${infer Rest}` ? Tokenizer<Rest, [...Tokens, { type: "slash" }]>

: Input extends `${infer Ident extends ValidIdentifier}${infer Rest}` ? Tokenizer<Rest, [...Tokens, { type: "identifier"; name: Ident }]>

: Input extends `${infer Num extends number}${infer Rest}` ? Tokenizer<Rest, [...Tokens, { type: "num"; num: Num }]>

: Tokens;Tokenizer is a recursive type that builds up an array of tokens by trying a ton of string patterns on the input. each pattern starts with the desired token and captures the rest to then call itself with. recursion stops when no pattern is able to be matched and returns the tokens we built up.

more languages should have string pattern matching. shoutout gleam for having exhaustive string pattern matching.

parsing

the parser is a recursive descent parser that follows this grammar.

program = (declaration)*

declaration = var | assignment | statement

var = "let" identifier "=" expr ";"

assignment = identifier "=" expr ";"

statement = print | block | expr-statement

print = "print" expr ";"

block = "{" (declaration)* "}"

expr-statement = expr ";"

expr = term

term = factor (("+" | "-") factor)*

factor = call (("*" | "/") call)*

call = primary ("(" expr? ")")*

primary = literal | identifier ("->" expr)? | "(" expr ")"expression and statement types are both discriminated unions again.

type Expr =

| { type: "grouping"; expr: Expr }

| { type: "add"; left: Expr; right: Expr }

| { type: "sub"; left: Expr; right: Expr }

| { type: "mul"; left: Expr; right: Expr }

| { type: "div"; left: Expr; right: Expr }

| { type: "literal"; num: number }

| { type: "identifier"; name: string }

| { type: "function"; argument: string; expr: Expr }

| { type: "call"; callee: Expr; argument: Expr | undefined };

type Stmt =

| { type: "declaration"; name: string; value: Expr }

| { type: "assign"; name: string; value: Expr }

| { type: "print"; expr: Expr }

| { type: "expression"; expr: Expr }

| { type: "block"; stmts: Stmt[] };each rule in the grammar gets turned into a type that takes in the current tokens and returns a tuple of the format [Expr | Stmt, NewTokens] or never in the case of an error. because we can’t mutate anything and only create new values, every rule has to return a new array of tokens.

here’s what the assignment rule looks like.

// identifier "=" expr ";"

type AssignmentDeclaration<Tokens extends Token[]> =

Tokens extends [{ type: "identifier"; name: infer Ident }, ...infer Tokens extends Token[]]

? Tokens extends [{ type: "equals" }, ...infer Tokens extends Token[]]

? Expr<Tokens> extends [infer Value extends Expr, infer Tokens extends Token[]]

? Tokens extends [{ type: "semicolon" }, ...infer Tokens extends Token[]]

? [{ type: "assign"; name: Ident; value: Value }, Tokens]

: never

: never

: never

: never;we pattern match on Tokens to check if we can eat up the desired token and define a new Tokens without the token we ate, and repeat that a ton.

zero error handling in non happy paths… oops

every grammar rule was pretty easy to translate except the ones involving loops like term, factor, and call.

// term = factor (("+" | "-") factor)*

// factor

type Term<Tokens extends Token[]> =

Factor<Tokens> extends [infer Left, infer Tokens extends Token[]]

? TermInner<Left, Tokens>

: never;

// (("+" | "-") factor)*

type TermInner<Left, Tokens extends Token[]> =

Tokens extends [{ type: infer Op extends "plus" | "minus" }, ...infer Tokens extends Token[]]

? Factor<Tokens> extends [infer Right, infer Tokens extends Token[]]

? TermInner<{ type: { plus: "add"; minus: "sub" }[Op]; left: Left; right: Right }, Tokens>

: never

: [Left, Tokens];i had to split these kinds of rules into two types because i couldn’t have part of a type loop.

here’s what a tiny program’s going to go through so far.

let x = 1;

print x + 1;[

{ type: "let" },

{ type: "identifier"; name: "x" },

{ type: "equals" },

{ type: "num"; num: 1 },

{ type: "semicolon" },

{ type: "print" },

{ type: "identifier"; name: "x" },

{ type: "plus" },

{ type: "num"; num: 1 },

{ type: "semicolon" },

];[

{

type: "declaration";

name: "x";

value: {

type: "literal";

num: 1;

};

},

{

type: "print";

expr: {

type: "add";

left: {

type: "identifier";

name: "x";

};

right: {

type: "literal";

num: 1;

};

};

},

];cool.

it was near this point programming where the TS language server started giving in on me. i did not get IDE errors anymore for things like calling a generic type with the wrong number of arguments and i would have to reload the file to recover from some syntax errors. here’s to hoping the TS Go rewrite reduces the use of “TypeScript: Restart TS Server” for everyone.

interpreting

the final challenge is here.

here’s EvalExpr v0.1. EvalExpr will recurse until it hits a literal, then work its way back up to compute nested expressions.

type EvalExpr<Node extends Expr> =

Node extends { type: "grouping" }

? EvalExpr<Node["expr"]>

: Node extends { type: "add" }

? Add<EvalExpr<Node["left"]>, EvalExpr<Node["right"]>>

: Node extends { type: "sub" }

? Sub<EvalExpr<Node["left"]>, EvalExpr<Node["right"]>>

: Node extends { type: "mul" }

? Mul<EvalExpr<Node["left"]>, EvalExpr<Node["right"]>>

: Node extends { type: "div" }

? Div<EvalExpr<Node["left"]>, EvalExpr<Node["right"]>>

: Node extends { type: "literal" }

? Node["num"]

: never;expressions run in an scope with local variables though, so let’s bring that in.

type Environment = {

enclosing: Environment | undefined;

locals: Record<string, Value>;

};each scope represents an environment pointing to a parent scope, or in the case of a global scope, none.

EvalExpr v0.2 now receives the current environment to do variable lookups.

type EvalExpr<Node extends Expr, Env extends Environment> =

// ...

Node extends { type: "identifier" }

? EnvironmentLookup<Env, Node["name"]>

// ...i’ll save you the details of EnvironmentLookup as it simply looks up a variable in the current and parent scopes.

we have statements to interpret too. you know how we can’t mutate anything? that means we have to treat our statement evalutator as a function that takes in our environment and print output, and returns a new environment and new print output. something like f(Env, Output) => [NewEnv, NewOutput].

type EvalStmt<Node extends Stmt, Env extends Environment, Out extends string[]> =

Node extends { type: "declaration" }

? [EnvironmentDeclare<Env, Node["name"], EvalExpr<Node["value"], Env>>, Out]

: Node extends { type: "assign" }

? [EnvironmentAssign<Env, Node["name"], EvalExpr<Node["value"], Env>>, Out]

: Node extends { type: "print" }

? [Env, [...Out, ValueDisplay<EvalExpr<Node["expr"], Env>>]]

: Node extends { type: "expression" }

? [Env, Out]

: Node extends { type: "block" }

? Eval<Node["stmts"], EnvironmentEnclosing<Env>, Out>

: never;both EnvironmentDeclare and EnvironmentAssign return new environments.

type EnvironmentDeclare<

Env extends Environment,

Name extends string,

Val extends Value,

> = {

enclosing: Env["enclosing"];

locals: Env["locals"] & Record<Name, Val>;

};

type EnvironmentAssign<

Env extends Environment,

Name extends string,

Val extends Value,

> = Env["locals"][Name] extends Value

? { enclosing: Env["enclosing"]; locals: Omit<Env["locals"], Name> & Record<Name, Val> }

: Env["enclosing"] extends infer Enclosing extends Environment

? { enclosing: EnvironmentAssign<Enclosing, Name, Val>; locals: Env["locals"] }

: never;something interesting is that when we evaluate an expression statement (Node extends { type: "expression" }), we just return [Env, Out]. because expressions just produce values and don’t change the state of our environment or our output, there’s no work to do.

the final type that drives it all is Eval, taking in some statements it will recurse with the output of EvalStmt until we don’t have any more statements and return the environment’s parent and output.

type Eval<

Stmts extends Stmt[],

Env extends Environment = { enclosing: undefined; locals: {} },

Out extends string[] = [],

> = Stmts extends [infer S extends Stmt, ...infer Stmts extends Stmt[]]

? EvalStmt<S, Env, Out> extends [

infer Env extends Environment,

infer Out extends string[],

]

? Eval<Stmts, Env, Out>

: never

: [Env["enclosing"], Out];the reason Eval returns the provided environment’s parent is to let EvalStmt to call Eval on a block statement with an new environment that encloses the current one, let it make any changes to the world, and give back the original environment.

// EvalStmt ...

Node extends { type: "block" }

? Eval<Node["stmts"], EnvironmentEnclosing<Env>, Out>

// call `Eval` with an environment enclosing `Env`, get back `Env` with any changes.conclusion

this is all just functional programming, every part of it. and it’s really cool honestly. the tokenizer, parser, interpreter, and everything inside are just pure transformations of some state to produce other state without any side effects, including mutation.

this whole project started when i was lying on my bed at 3 am and thought it would be cool to make a language in a functional programming language after reading Crafting Interpreters. i’m a bit lazy cause i didn’t want to learn a new language and wondered if it would be possible in type-level TS. i was right.

credits

TLTSS’s language design and implementation is heavily influenced by Crafting Interpreters’s Lox language, go read it.